God and Starbucks Read online

Page 7

“Well, my role will probably be like an old chore that my mother gave me that I really didn’t like all the time, but I accepted it, and that’s to feed the dog.”

The comment naturally was met with laughter; Jon knew how to tell a joke and to work a crowd. He didn’t mean anything by it, and in fact there was truth in his statement. That is precisely the role Jon would have with the Bucks: to support Glenn Robinson. For some reason, though, it bothered me to hear him say it.

What about me, Jon? What about feeding your bro?

I was a little icy toward Jon for a while after that, and he responded in kind. Tension mounted over the course of several weeks, and finally spilled over one day in practice when Jon grabbed a rebound near me and swung his elbows wildly after corralling the ball. Now, flying elbows are a part of the game in basketball, but there is an unspoken rule among players about when and how flagrantly they can be utilized (there are some very clear and concise rules set down by the NBA as well, but that is a different matter entirely). Clearing space and sending a message is one thing, especially in a game, but deliberately swinging your elbows in the vicinity of a teammate’s face in practice? That’s a problem.

As we ran down the court together, I let Jon know exactly how I felt.

“Yo, JB . . . watch your ’bows, man.”

Jon did not even make eye contact. Instead, as he backpedaled, he said, “Fuck you, Vinnie. I’ll do what I want to do.”

From there things escalated quickly. We had passed the point of settling our differences like adults. Now we were like a couple of kids on the playground, where you never call fouls and basketball games frequently devolve into fistfights.

Another missed shot, another aggressive rebound by Jon, with me right next to him, and another flying elbow. This one nearly clipped me in the face. Rather than passing the ball ahead, Jon began dribbling. He raced up the court as quickly as he could, obviously intent on trying to score and make me look bad. So I went after him. As he crossed midcourt I caught up to him and cracked him in the back of the head with my forearm. The ball went one way, Jon and I went another. We both spilled to the floor and commenced wrestling like fools. I had seven inches and nearly fifty pounds on Jon—although I wasn’t ordinarily as feisty as he was—and quickly gained the upper hand by putting him in a choke hold. Never before had I felt that much rage, and I don’t even know where it came from. It was similar to the sort of thing I used to feel in college, when I would get chewed out in practice, except now I wasn’t responding with tears of frustration. Now I lashed out.

“Jesus, Vinnie, get off me!” Jon screamed. “You’re breaking my neck!”

I did not get off him. I did not loosen my grip until one of our assistants, Butch Carter, leaped onto my back and physically pried my fingers from Jon’s throat. I rolled over, scrambled to my feet, and ran straight to the locker room, where I punched a wall and broke down in tears. I felt such a complicated swirl of emotions: anger at Jon’s provocation, disappointment in myself over having nearly hurt my friend, and surprise that I had so quickly lost all composure. In general, I just felt . . . bad. I was embarrassed. But not everyone thought it was such a terrible thing. The guys on the team mostly responded with amusement. And the coaches? While they did not condone fighting among teammates, they certainly did not object to seeing laid-back Vin Baker express a more violent and aggressive side.

“Man, I’m sorry,” I said through glassy eyes when Butch tracked me down. “There’s no excuse for that.”

Butch patted me on the back. “It’s okay, Vin. Don’t worry about it. Shit happens.” Then he laughed, and moved in closer, so that he could almost whisper in my ear. “I’ll tell you something else—you’d better not change.”

I got the message, loud and clear. While no one on the coaching staff was going to advocate wrestling matches among teammates, they were not unhappy to see a little fire out of a guy who had often been branded too nice for his own good. I just had to be more consistent in channeling my anger in productive ways.

There was no lingering bad blood between JB and me. He was my boy and there was no way I was going to let a fight ruin our friendship, although I’ll admit to feeling uncomfortable when we got on the team bus the next day. I thought he might be mad at me. Given the circumstances, I wouldn’t have blamed him. I could have seriously hurt Jon, and if that had happened, I don’t know if I could have forgiven myself. But Jon took the high road. He was one of the last players to board the bus, and I was already seated near the back. I could see him scanning the rows looking for something as he slowly made his way down the aisle. When our eyes met, he nodded and smiled, quickened his pace, and made his way to my seat. He sat down next to me. For a moment we sat in silence. Then Jon broke the ice.

“Here, bro. I got something for you.” He reached into his bag and pulled out a portable DVD player. In 1994, before the advent of streaming video and iPhones and iPads, portable DVD players, with flip tops and tiny screens, were a miracle, coveted by anyone who spent long hours on the road with no easy way to fill the travel time. “I know you don’t have one,” Jon added. “Hope you like it.”

It’s not like I couldn’t afford my own portable DVD player, but that wasn’t the point. I didn’t have one, and I had spoken admiringly of the devices owned by some of the guys on the team. I just hadn’t gotten around to buying one. Jon remembered this, and took care of it for me.

“Thanks, JB,” I said, before adding, “My bad about yesterday.”

Jon waved a hand dismissively. “Come on, man. Whatever. Forget about it.”

When Todd Day got on the bus a few minutes later and saw me playing with my new toy, he was instantly intrigued. It had been kind of a running joke on the team that I had this big contract but wouldn’t spend any money. No fancy cars, no mansion, nothing. And everyone knew that I didn’t do electronics. I could barely figure out the remote on the modest little TV in my apartment. So Todd was naturally surprised.

“What the hell is that?” he said.

“Oh, it’s just one of those little portable DVD players.”

Todd smirked. “I know what the fuck it is, man. I mean, where did you get it? You don’t buy shit like that.”

“Yeah, JB got it for me.”

Todd did a double take, looking toward the front of the bus, then at me, then toward the front again. On his face was an expression of utter exasperation.

“What the fuck?! Who? I mean . . . you guys were trying to kill each other yesterday in practice.”

I nodded. “Uh-huh.”

“Damn,” Todd said, shaking his head in disbelief. “I might have to beat JB, too.”

“Come on, TD. Knock it off. That’s not funny.”

“Nah, man. I’m serious. I’m gonna kick his ass tomorrow. I need a new cell phone.”

I became one of Glenn Robinson’s closest friends on the Bucks, although I can’t honestly say that I got to know him all that well. Dog was a little weird, kind of an introvert, so you couldn’t really sit around with him and have deep conversations about stuff. We bonded first on the court; whatever jealousy I may have harbored toward Dog because of his status as a number one pick and franchise savior, there was no questioning the guy’s ability as a basketball player. We both viewed ourselves as alpha males within the context of the team, and ordinarily that can present problems. But for some reason we got along great and figured out our respective roles. I was kind of like Scottie Pippen to Glenn’s Michael Jordan. I was a star on the Bucks; Dog was the star. And that was fine with me. Dog could score like few players I had ever seen, and I felt privileged to play alongside him. The guy was ridiculously gifted from an offensive standpoint. I made peace very early in Dog’s tenure that he’d be our leading scorer and offensive threat.

I could score, too, but not like Glenn. I did other things. I could block shots and rebound. I played defense and passed the ball. So we became boys because our stats began lining up in a complementary fashion. We played well toget

her and we understood each other. It was a comfortable relationship, and it led to our hanging out a bit off the court as well. Now, I knew that Dog liked his weed—a lot. And as we began spending some time together I came to see that smoking was his primary recreational activity. He didn’t drink much, didn’t like to go out to clubs. He just liked to chill at home with some friends and get high. That was his thing, and it was one of the reasons he was considered such an enigma.

I joined Dog on occasion, maybe once a week early in the season. Pretty soon, once a week became twice a week. Then three times a week—in addition to going out with the guys and hitting strip clubs when we were on the road. I was drinking and smoking weed, although I wouldn’t call my use of either excessive. And I was playing very good basketball, so there were no indications that I was out of control or otherwise compromising my basketball career. Just the opposite, in fact. Even as I dabbled a little more extensively with drugs and alcohol, my performance improved. I averaged 17.7 points and 10.3 rebounds per game in my second season, and was named to the NBA All-Star team for the first time. Go figure.

It’s tempting to connect dots that should not be connected, to look for a causal relationship where one does not exist—or where the relationship is tenuous at best—and I certainly did that where marijuana was concerned. Initially there were a few simple things I liked about smoking weed: the gentle euphoria and the slipping away of anxiety; the quiet camaraderie of hanging out with a small group of buddies, watching TV, and getting high; and the inevitable food binge that came afterward. I love eating—always have—and smoking turned me into an eating machine. And in the beginning, at least, I picked my spots carefully, smoking only on off days or after practice, and only lightly, just enough to get a little buzz. The great thing about weed is that not much is required to reach a state of mild inebriation. And hangovers are practically nonexistent. In that sense, it’s a far better match for the athlete’s lifestyle than alcohol is. On the downside, alcohol is predictable: you know how much you can drink, and what the effects are likely to be. Back in those days, when weed was illegal nationwide, it was a mystery: you never knew exactly what was in it, or the level of THC, or the kind of trip you might experience. You could smoke an entire joint and be only slightly buzzed, or you could take a single hit and be incapacitated. Every high was an adventure.

Knowing the risks, I abstained from marijuana for roughly twenty-four hours before a game or practice. And usually more like forty-eight hours. That was my routine, and I thought it was one embraced by just about all the guys in the league who liked to smoke. I mean, who would be crazy enough to play while high?

The answer came one day at Glenn Robinson’s place, during my third season with the Bucks. I still remember the date: January 5, 1996. We had a home game scheduled that evening against the Portland Trail Blazers, so as always there was a morning shootaround. Afterward I went back to Dog’s house to hang out and get a haircut (this was not uncommon—we’d hire someone to come to the house rather than going out and dealing with fans). It was just me and him and a few of his boys from back home—sometimes it seemed like Dog had half of Gary, Indiana, living with him. I don’t even remember who broke out the weed. I just remember smelling it while I was getting my haircut. Out of the corner of my eye I could see the joint being passed around, and I remember feeling very curious about what would happen when it got to Glenn. By this point I knew that Dog was a heavy smoker, but I figured smoking on game day was a line you simply did not cross, no matter how much you liked weed. I tried to turn my head enough to see what was happening and got scolded by the girl cutting my hair, but I caught a glimpse of Dog taking the joint in hand, pressing it to his lips, and inhaling deeply.

What the . . . ?!

Glenn was such a good basketball player, and such a phenomenal athlete, that I couldn’t imagine him taking a chance like this. But the truth is, his demeanor was so nonchalant that there was no mistaking this as anything but part of his normal game-day routine.

“Dog,” I said, trying not to sound judgmental. “You smoke before games?”

He shrugged. A thin, tight-lipped smile crossed his face. I checked the clock. It was around 11:30 a.m. Game time was 7:00 p.m.; we weren’t due at the arena until five o’clock. That left more than five hours for Dog to get sober. I figured it wouldn’t be a problem, especially since he obviously knew what he was doing. I had no intention of taking a similar risk, but when the joint came to me, instead of waving it off and saying thanks, but no thanks . . . I hit it.

Instantly I was overcome with regret. Marijuana is like a scratch-off lottery ticket, and this time I’d hit the jackpot.

Oh, no . . . what did I just do?

The high was instantaneous and potent. I felt a surge of anxiety about getting caught when I showed up that night, so I did the logical stoner thing: I tried to squelch the anxiety by smoking even more! The joint came around and I hit it again. And again . . . and again. At least five times. I don’t remember the exact number, but I do know that by the time we were through, I was wasted.

Gone, however, was the anxiety and the sense of dread about getting caught; I was too messed up to care. Plenty of time, Dog said. You’ll be fine. We went out, got something to eat, and then I went back to my apartment to take a nap. I figured I’d wake up sober and rested and ready to play.

Instead, when the alarm went off at four, my head was full and foggy. I wouldn’t say I was completely inebriated, but I definitely still felt the effects. I knew the feeling intimately, and it was still lingering. I drove to the arena (that’s right—one of hundreds of episodes of my driving under the influence, any one of which could have gone horribly wrong) and prepared to play. I went through my usual pregame routine: stretching, relaxing in the Jacuzzi, shooting, low-post moves—and still I was high. But you know what else? I felt comfortable. I mean, I was . . . relaxed. I didn’t feel paranoid or anxious. I just went out and played. Oh, man, did I play! That night I had 41 points and eight rebounds, and we beat the Blazers by 17—the most lopsided victory of the season (we didn’t have a lot of victories that year, let alone blowouts). It was the best game of my entire career.

Talk about validation.

The truth, of course, is that there was no correlation at all. I had the talent to put up those kinds of numbers; it just hadn’t happened yet. Now it had, and in that superstitious way of all athletes, I tried to link cause with effect. It became a self-fulfilling prophecy: I’m going to smoke weed every day . . . make it part of my pregame regimen! I remember thinking in the middle of the game, I’ve got to do this. This is what it is. This is what I’ve been missing!

After that, Glenn and I became even tighter. I sought him out every day, whether we had a game or not. Seemingly overnight, I went from a casual smoker of weed to a habitual smoker. It was that fast. Maybe marijuana is not physically addictive the way opioids and alcohol are addictive—you don’t experience the agony of withdrawal when you stop, but when you’re used to smoking every day, and you suddenly stop, you do crave the effects; you miss the high. Whether that is a psychological or physiological addiction, I don’t know, but it’s real, and it can wreak havoc on your life.

Dog and I became virtually inseparable, especially on game days. After that night against Portland, I got high before every game for the remainder of the season, with one notable exception: the NBA All-Star Game, which was played in Phoenix that year. I was selected to play for the second straight year. For some reason I worried about playing high that night. It was a big game with a national television audience, and I fretted about the possibility of making an error in calibration or getting weed laced with some sort of foreign substance. Better to just play sober, I thought. I played twenty-four minutes in the All-Star Game and did not distinguish myself in any way. I had six points and two rebounds—hardly memorable numbers. I came away more convinced than ever that I was a better basketball player when I was high.

I also knew that I had crossed a barrie

r, and that most of the guys on the team would neither understand nor approve of my behavior. Todd Day loved weed, but I never saw him, or anyone else, get high before a game. This was just between Dog and me, and we did our best to keep it that way. I’d go to his house on game days when we were in Milwaukee; on the road I’d go to his hotel room. It was a quiet and secretive ritual. If someone knocked on the door while we were smoking—which happened quite a few times—we’d look at each other and hold our breath, as if to say, Can’t let him in. Can’t let anyone else in the room.

I think a lot of guys on the team, and probably some of the coaches, suspected that Dog was lighting up before games; it was a major component of his lifestyle, and everyone knew it. But when you’re playing well—and Dog was playing very well—people tend to overlook things. That I was his partner in game-day smoking was less well known, if it was known at all. I did not share this news with anyone, out of fear that I would be exposed and branded as unprofessional. I was extremely cautious. Even when I was out drinking with the boys after a game I would not let it slip.

Nope . . . couldn’t take that chance.

This was my dirty little secret. And I owned it.

6

Scared Straight (Almost)

By the end of my third year, I was one of the most productive frontcourt players in the league, an acknowledged all-star who could give his team 20 points and 10 rebounds just about any night of the week. Those are the kinds of numbers that people notice and that invariably lead to a feeding frenzy in free agency. In terms of basketball, things could not have been much better. I loved the game and I was having fun playing at a level that I wasn’t even sure was attainable.

I was also a total weed-head.

I rarely drank or even went out much anymore. Alcohol is a far more social drug than marijuana, in part because of its legality, but also because it works as a social lubricant. When I would drink, I wanted to hit the clubs and be the life of the party. When I’d smoke, I just wanted to chill and hang with a couple of my boys. It didn’t take long to reach the point where the sober hours were outnumbered by the inebriated hours. I hardly ever went out during this period, and when I did, I’d nurse a drink for a couple of hours, just to have it in my hand and keep people from questioning me; I didn’t want to look out of place.

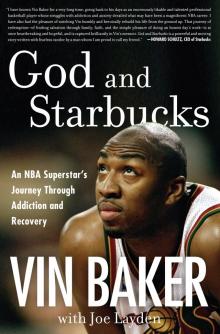

God and Starbucks

God and Starbucks